Executive Summary

As employers and health plans purchase more digital health solutions for their members, they increasingly seek to tie payments to measurable outcomes using performance-based contracts (PBCs).

In traditional contracts, purchasers often reimburse digital health vendors on the basis of the number of program participants (e.g., per member or user per month fees). Under a performance-based contract, some or all payments to vendors are contingent upon prespecified outcomes, such as clinical improvements, engagement rates, or cost savings.

While interest in PBCs is common among purchasers, executing these contracts remains challenging—particularly for employer benefits teams who have limited capacity to negotiate and adjudicate complex contracts. Further, purchasers want to move away from easier-to-measure satisfaction and engagement-based success metrics, in favor of more meaningful—but harder to measure—clinical and financial outcome measures.

Purchasers want to ensure that they are getting value from their digital health solutions. A well-structured performance-based contract can:

- Help purchasers see their desired outcomes by tying payment to measurable results.

- Generate new data that supports ongoing evaluation of digital health solutions and continuous improvement of contracting models.

- Allow high-performing digital health vendors to distinguish themselves in the market. Many digital health companies are embracing this shift by offering new pricing models that tie larger portions of fees to these validated metrics.

The report:

- Synthesizes market insights,

- Highlights leading practices,

- Introduces contracting toolkits for four high-impact clinical areas, and

- Discusses ways for purchasers and vendors to further refine their contracting models.

This playbook and associated contracting toolkits offer a practical roadmap—grounded in the experiences of leading employers, health plans, and digital health vendors—to help stakeholders align incentives, define meaningful outcomes, and scale solutions that deliver measurable, cost-effective impact. Thoughtful PBCs can ensure that digital health solutions not only promise transformation, but consistently deliver it.

Explore interactive toolkits

To support adoption of performance-based contracts, PHTI has developed interactive contracting toolkits to offer guidance on how to execute a performance-based contract in four clinical areas that have been evaluated by PHTI:

Toolkits for Specific Clinical Areas

To support adoption of performance-based contracts, PHTI has developed interactive contracting toolkits to offer guidance on how to execute a performance-based contract in four clinical areas that have been evaluated by PHTI: Digital Diabetes Management , Virtual Musculoskeletal Solutions, Digital Hypertension Management, and Virtual Solutions for Depression and Anxiety.

These toolkits were designed to promote meaningful risk for the digital health vendor and budget predictability for the purchaser, provide clarity on key definitions, minimize administrative burden, and embed reciprocal data-sharing commitments. Each toolkit has been vetted and refined through direct engagement with leading employers, health plans, and vendors representing each clinical area. They incorporate feedback from both sides of the negotiating table on what is feasible to implement at scale.

Organizations may use these toolkits as a starting point to:

- Standardize core elements of their contracting strategy across vendors

- Promote alignment around engagement and outcomes metrics

- Reduce time spent on initial contract negotiations by creating standard definitions and starting contract terms

- Ensure that key operational and data-sharing protocols are clearly articulated

Digital health vendors can also use these contracts to better understand purchaser expectations; strengthen their contracting readiness; and align pricing, reporting, and performance measurement with market norms.

The content of this playbook/report and its associated toolkits has been prepared by PHTI for informational purposes and does not constitute legal, medical, clinical or other professional advice. PHTI cannot make any guarantees or warranties regarding results from the use of such content. The content is not intended to replace thoughtful customization and drafting addressing an organization’s specific objectives and circumstances. All companies, specific products or case studies mentioned are for explanatory purposes only.

Performance-based contracting is no longer aspirational—it is table stakes.

Purchasers now expect evidence of clinical and financial impact, and PBCs provide the framework to deliver it.

Key Findings

The State of Performance-Based Contracts

Key Contracting Decisions

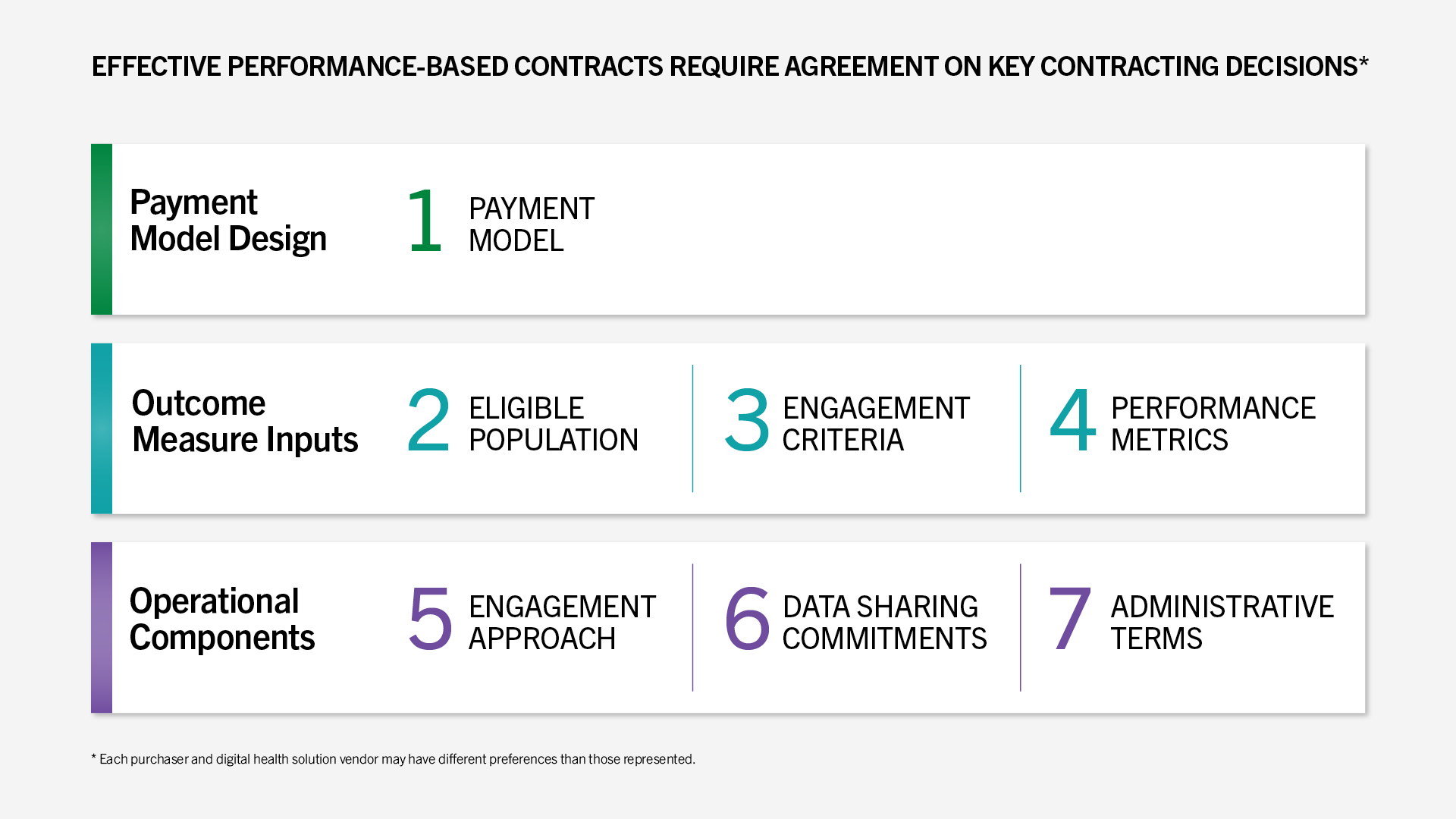

Negotiating effective performance-based contracts requires coming to agreement on a payment model, outcome measures, and various operational components of the contract.

The Value for Vendors

For vendors, the playbook offers a clear window into purchaser expectations and the contracting features that matter most in procurement decisions.

By aligning their pricing models, performance metrics, and reporting capabilities with these contracts, vendors can strengthen their value proposition, differentiate themselves in competitive evaluations, and position their products for long-term partnerships grounded in measurable outcomes. Contracts can then be fine-tuned to align more closely with each purchaser’s strategic goals.

When executed well, performance-based contracts reinforce that both parties are working toward the same goals: improving health, expanding access, and delivering value.

Challenges and Opportunities

Digital health solutions hold great promise to address some of the most persistent and costly challenges in healthcare, from closing access gaps in behavioral health to improving chronic disease management at scale, while also offering the potential to reduce overall cost of care. As these tools become more central to care delivery, employers and health plans are increasingly turning to performance-based contracts to ensure that solutions deliver desired outcomes.

We were excited at first [about PBCs], but it became clear we couldn’t keep up with the validation piece. So now we’re more cautious.

Suzanne Usaj, Wonderful Company

A Market Shift Toward Greater Accountability and Risk-Sharing

These contracts—which tie payment to specific performance metrics, such as clinical outcomes, member engagement, or cost savings—reflect a broader market shift away from per member per month (PMPM) pricing toward greater accountability and risk-sharing for digital solutions, and toward value-based care more broadly.

Purchasers have become more discerning in purchasing and contracting for new technologies. Many are increasingly skeptical of vendor-reported outcomes—especially when outcomes are based on vendor-proprietary data or measurement methodologies, ambiguous engagement metrics, or unverifiable cost-avoidance claims. Instead, purchasers are seeking stronger evidence of clinical effectiveness and financial returns.

Most of the ROI analyses we get are built by the vendors themselves, using assumptions that make them look good. There’s no way we can validate those claims internally.

Nathan Counts, Amtrak

Employers acknowledge the importance of digital innovation and are eager to partner and scale solutions but are also facing pressure to demonstrate return on investment.

We go into these relationships expecting [the digital solution is] effective, but we need ways to know whether it is.

Luke Prettol, AT&T

In response, vendors are evolving their sales model, and a growing number publicly assert that 100% of their fees are at risk or that they guarantee multiple returns on investment.

The Challenges of Implementing Performance-Based Contracts

Despite interest in PBCs from both sides of the market, executing and implementing these contracts remains difficult. Challenges include:

- Information asymmetry between the purchaser and vendor

- Limited access to high-fidelity data on meaningful performance

- A lack of transparency when data are available

- Misaligned incentives

While large or well-resourced employers and plans may have the analytic capabilities and infrastructure to assess impact, smaller purchasers are often unable to do so independently.

Third-party platforms have emerged to aggregate digital health solutions, allowing plans and employers to streamline procurement. While these aggregators can simplify contracting and implementation, they do not eliminate the need for purchasers to set clear expectations or negotiate meaningful performance terms up front. In many cases, the aggregator’s contract becomes the conduit for holding vendors accountable, making well-structured PBC frameworks even more important. Purchasers that rely solely on aggregators without defined performance criteria risk losing transparency into outcomes and diminishing their ability to assess impact across solutions.

Performance-Based Contracting: The Opportunity

Purchasers adopt digital health solutions for goals that range from enhancing the user experience to expanding access, improving clinical outcomes, and reducing costs.

Many purchasers are seeking technologies that improve population health and deliver outcomes equal to or better than traditional care models, particularly in high-cost, high-need clinical areas.

At the same time, employers competing for top talent and health plans competing for member enrollment view digital health solutions as a way to enhance the user experience, improve engagement, and support retention. In many cases, these tools also help close access gaps by offering convenient, timely, and often virtual care options.

As a result, contracting goals vary on the basis of each purchaser’s clinical strategy and member needs, and many seek to advance multiple objectives—cost, outcomes, access, and experience—through a single solution.

Augmenting vs. Replacing In-Person Care

Purchasers evaluate digital health solutions on the basis of the type of impact they are expected to deliver—whether through cost savings, improved outcomes, or expanded access. Solutions that replace in-person care often have a clearer ROI pathway because they can directly substitute lower cost virtual or hybrid models for traditional brick-and-mortar care models; however, they must still demonstrate clinical quality that meets or exceeds traditional standards. As one representative from a digital health solution vendor explained, “When a solution is replacing care, the buyer expects a higher standard. If you’re the clinical front door, you have to prove you’re doing what a provider would do.”—Dickon Waterfield, Lantern

Solutions that complement in-person care—such as remote monitoring or digital chronic condition management programs—risk being cost-additive in the near-term, but can improve outcomes and adherence, which can contribute to longer-term cost reductions. For these solutions, purchasers often focus PBC terms on metrics such as member engagement, workflow completion, or intermediate clinical indicators that reflect early progress toward better health outcomes.

Purchaser Goals Drive Contracting Decisions

Click to see definitions of success, examples, and metrics

Performance-Based Contracts Create Clarity and Accountability

Performance-based contracts are particularly useful in scenarios where there is uncertainty about a product’s impact. Uncertainty may stem from limited evidence of clinical efficacy, unclear differentiation across vendors, unknown durability of impact, or questions about which patient populations are most likely to benefit. Additionally, purchasers are interested in solutions that sustain patient engagement over time, recognizing that many interventions demonstrate impact only when used consistently. In these contexts, PBCs serve as a tool to mitigate purchaser risk and strengthen accountability. Over time, these arrangements also generate the real-world data needed to assess impact more confidently, refine contracting terms, and inform future purchasing decisions.

For digital health vendors, PBCs provide an opportunity to differentiate themselves by demonstrating confidence in their outcomes. If vendors need additional avenues to produce data, then PBCs also provide the opportunity to validate performance in partnership with purchasers.

Key Contracting Decisions

Designing an effective performance-based contract requires careful decisions about what to measure, how to measure it, and how to tie payment to those results. Each purchaser must grapple with a core set of questions:

- Why are we implementing this solution?

- Who do we want this to serve?

- What level of risk are we comfortable with?

Purchasers of different sizes and capabilities all must navigate seven recurring decision points across three domains of performance-based contracting: 1) selecting a payment model, 2) determining inputs for outcome measures, and 3) selecting the operational components of the contract. Many of these decisions come with trade-offs, such as sacrificing specificity to reduce administrative burden, or prioritizing predictability at the cost of vendor accountability.

The following sections outline leading practices for structuring each element in ways that balance accountability, feasibility, and impact.

Payment Model Design

This section addresses how payments can be structured to meaningfully tie contract value to performance while preserving predictability and feasibility.

Payment Model

To effectively design a payment model, purchasers and vendors must balance the goals of rewarding performance, minimizing administrative burden, and avoiding perverse incentives such as cherry-picking members who are easiest to engage or most likely to achieve positive outcomes.

Value predictable payments that incentivize outcomes and hold vendors accountable.

Prefer upfront payment structures or clawbacks that support stable cash flow and enable investment in delivery.

Purchasers must be able to define what outcomes they seek to achieve, vendors must detail what they are able to deliver, and infrastructure for tracking the metrics that drive payment must exist on both sides of the negotiating table.

Many PBCs today use a clawback model, in which vendors are paid up front, with the understanding that funds will be returned if previously agreed-upon performance guarantees are missed. This structure maximizes vendor cash flow and offers purchasers budget predictability.

In practice, though, clawbacks are rarely enforced as written. Underperformance is often averaged across the total population, which can obscure variation in results—strong performance among some members may offset poor outcomes among others, even when aggregate targets are missed. As a result, vendors may appear to meet benchmarks that only a subset of participants actually achieved. This creates misaligned incentives for how vendors allocate resources, and shortfalls are typically rolled into discounts on future invoices rather than refunded. Purchasers report that this undermines accountability and creates friction with vendors, particularly at the end of a contract.

As a result, many purchasers and vendors see a stronger alternative in a two-stream payment model that splits engagement from performance payments: Vendors receive a lower base fee tied to meaningful engagement, with the performance component withheld until outcomes are achieved. This approach preserves some vendor cash flow while ensuring purchasers only pay for demonstrated results.

Case Study

Structuring Payments Around Clear Purchasing Goals

BJ’s Wholesale Club employs a predominantly hourly workforce and sought to make behavioral health care more affordable and accessible for members. Because access—rather than clinical outcomes—was the company’s primary objective, it prioritized vendor partnerships that emphasized broad coverage and ease of entry over aggressive performance-based risk.

Working through its benefits consultant, the purchaser issued RFPs requiring vendors to outline expected enrollment, utilization, and engagement-funnel metrics. The purchaser then used its own claims data to validate those assumptions and convert them into measurable contract targets.

Reflecting its goals, the resulting contracts placed greater weight on upfront fees and a smaller portion on performance-based payments. This approach ensured vendor accountability for access and engagement metrics without disincentivizing participation in a high-need population.

I’ve never seen a clawback that wasn’t contentious.

Executive at large national health plan

Explore example approaches to structuring payment models

Click each clinical area to access the interactive toolkit.

Outcome Measure Inputs

This section focuses on defining what performance is measured and for whom, including eligible populations, thresholds for engagement, and clinically meaningful outcome measures that are feasible to collect, validate, and adjudicate.

Eligible Population

The eligible population includes all members who can access the solution, typically defined by clinical criteria (e.g., diagnosis), demographics (e.g., age), or utilization history (e.g., multiple physical therapy sessions in the past month). Eligibility determines who may engage with the solution and for whom outcomes may be measured.

Seek to balance broad access with avoiding payments for members unlikely to engage or benefit.

Favor inclusive eligibility definitions to maximize reach and ensure that more members have access to services.

Broad eligibility criteria can increase the total addressable population; however, and especially in payment models where fees are tied to eligibility, purchasers may end up paying for members who are unlikely to benefit from or engage with the solution.

Conversely, more targeted/narrower eligibility criteria focus efforts on those most likely to benefit but risks excluding members who may still receive value from the service.

The breadth of the eligible population will also impact the challenges associated with attaining targets for performance metrics. For example, narrower criteria focused on higher acuity populations may set the vendor up for success in metrics like PHQ-9 or GAD-7 scores. Higher acuity patients may be more likely to see a significant improvement in clinical measures or experience more regression to the mean. However, broad populations introduce the risk of spending on services for individuals who have less unmet need for the solution and may not be advisable for purchasers hoping to focus resources on the highest acuity or highest cost individuals.

Our guarantees are measured at the population level. We tried individual-level guarantees early on, but it became operationally messy. Purchasers value predictability, so structuring risk across a cohort keeps the contract simple and the incentives clean.

Virta

Often prefer broad eligibility to ensure access for all members, even if outcomes are later assessed for a more targeted subset.

May have more flexibility to define narrower populations, derived from risk stratification insights based on detailed, longitudinal claims data.

Explore example approaches to defining eligibility

Click each clinical area to access the interactive toolkit.

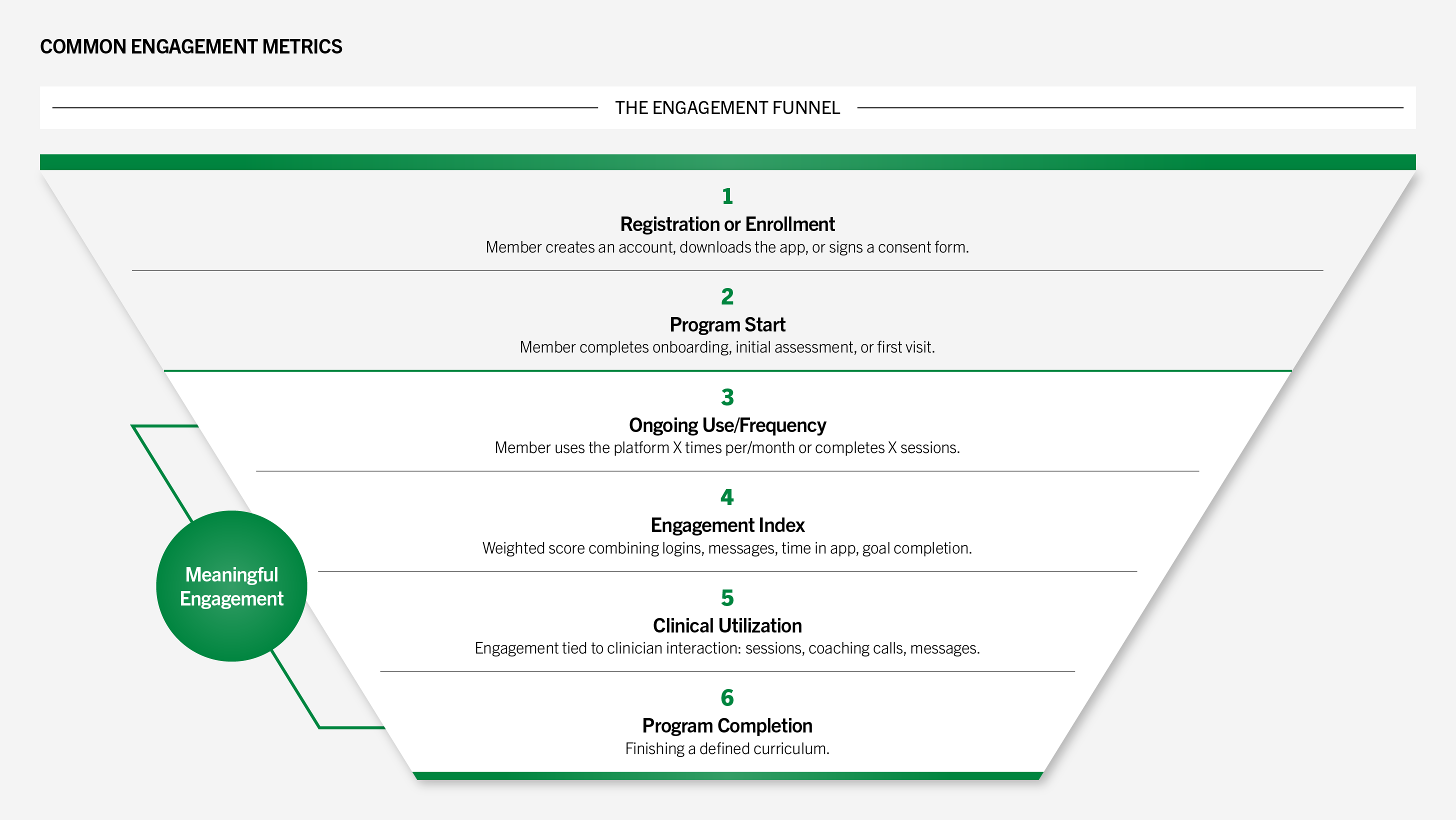

Engagement Criteria

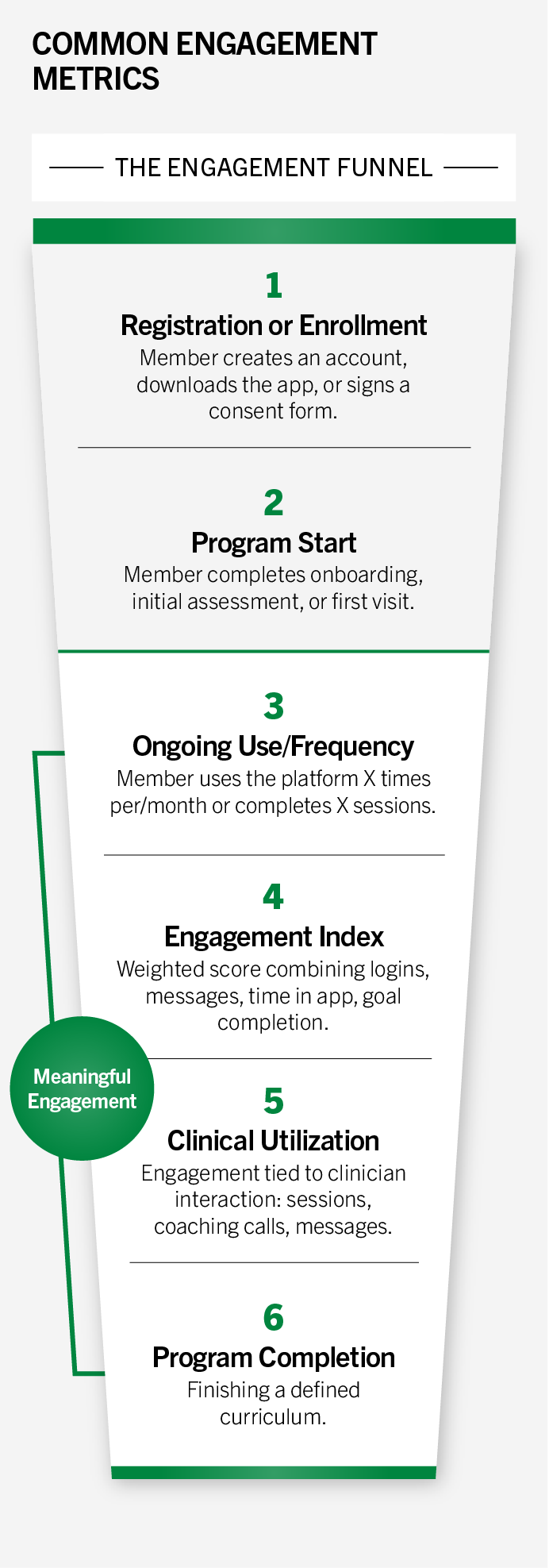

“Engagement” describes which members are actively using a vendor’s service. While engagement may be the primary goal of the purchaser in areas where access is an issue, in some instances, it is a necessary precursor to achieving meaningful clinical or financial outcomes.

For example, a patient may need to be consistently engaged over several months to achieve improvement in HbA1c. Definitions of engagement vary widely, ranging from patient “awareness” (e.g., enrolling in a solution or downloading an app) to more meaningful interactions, like the completion of three virtual visits with care team members.

Want strict, outcome-linked engagement thresholds to avoid paying for superficial interactions.

Emphasize capturing a range of engagement signals, recognizing that early or light-touch interactions can be important precursors to deeper participation.

While awareness and eligibility metrics are often easier to collect and report, purchasers increasingly indicate that they prefer more meaningful engagement metrics, especially as engagement metrics often serve as the basis for per engaged member per month (PEMPM) payments or eligibility for outcome-based bonuses.

And I’ve seen everything from super high-quality engagement where I have one vendor right now whose definition of engagement is that the individual engages with the app on a daily basis 80% of the time or more. And if not, they are not considered engaged. And if they are not engaged, we don’t pay. What I can’t get behind is … a solution that calls patients on the phone or sends them a form and if they pick up once or randomly fill out the form once, they are considered engaged.

Kate McIntosh, MD, Health New England

Without a shared standard, broad definitions (e.g., opening an app or an email without further activities) may result in purchasers paying full fees for members who derive little to no clinical benefit. Both vendors and purchasers are increasingly recognizing the need for greater specificity and alignment when defining contractual engagement terms.

So, if the vendor says, ‘we want you to give us engagement credit just for opening the app’, we’d say ‘no, let’s get the patient towards something that really matters.

Executive at large national plan

Common Engagement Metrics

Metrics at the bottom of the engagement funnel typically represent more meaningful levels of engagement.

Explore examples of defining engagement criteria

Click each clinical area to access the interactive toolkit.

Performance Metrics

Selecting metrics that are both meaningful and actionable is a persistent challenge in performance-based contracting. While purchasers often look to established frameworks—such as NCQA’s HEDIS measures or CMS quality benchmarks—for credibility and consistency, these metrics may not fully capture the nuances of digital health interventions.

Prioritize validated, clinically credible measures with transparent data sources and calculation methods.

Advocate for measures that are feasible to collect within their platforms and still meaningful for tracking progress.

Translating research-grade metrics into operational contracts can be difficult.

While measurement science emphasizes the importance of validity, reliability, and feasibility, many digital solutions lack standardized methodologies or interoperable data. This creates very practical challenges for purchasers: Who is responsible for calculating the measure? Who controls the underlying data? Is the information delivered in a timely way? In some instances, payers are running pilots to test measurement approaches and establish clear baselines before entering into a long-term agreement.

Without clear answers to these questions, even well-intentioned contracts risk misinterpretation or misaligned incentives.

Case Study

Using Pilots to Validate Performance Metrics Before Scaling

Health plans are increasingly using structured pilots to evaluate vendors before entering full-scale contracts. One national Medicare Advantage plan employs a three-phase, stage-gated process to test operational readiness and clinical impact. Early pilots focus on feasibility, by assessing data-sharing capabilities, engagement-funnel performance, and vendor responsiveness through weekly operational meetings. Only vendors demonstrating strong performance and adaptability advance to larger pilots that test outcomes more rigorously.

Similarly, one regional plan has implemented randomized rollout pilots, assigning some members to receive a solution, while others serve as a control group. This experimental design allows the plan to isolate vendor impact on utilization and clinical outcomes, rather than relying solely on engagement metrics.

Across both models, the pilot process enables purchasers to identify which vendors deliver measurable outcomes for specific populations, particularly where digital health solutions were originally built for different markets. By grounding contracting decisions in pilot data, purchasers reduce risk and ensure that performance metrics in scaled contracts are both evidence-based and achievable.

Are unlikely to utilize pilots because of concerns about access exclusions and more limited resources for cohorting and analysis.

Are more likely to employ pilots to study impact and refine implementation before scaling more broadly.

What is the “right” data source and metric?

For clinical outcomes, biomarker-based metrics with nationally recognized definitions (e.g., laboratory reported HbA1c, or hypertension control) are the gold standard, but they do not always exist or may be inaccessible via relevant data sources, leaving purchasers and vendors to rely on patient-reported outcomes metrics (PROMs) as proxies.

A critical consideration is the distinction between validated and unvalidated measurement tools. Instruments like the PHQ-9 or GAD-7 for anxiety and depression carry established clinical validity based on peer-reviewed studies, whereas vendor-designed patient surveys typically do not.

Even when validated scales exist for patient-reported outcomes, contract language should specify standardized survey administration to preserve reliability—for example, administration by an independent survey vendor or a clinical staff member following a defined protocol.

Selecting effective metrics requires balancing scientific rigor and operational pragmatism, along with transparent definitions. For financial outcomes, savings projections or proxy measures such as change in self-reported surgical intent are not advised. ROI should serve as the basis for PBCs only when a statistically valid, propensity-matched cohort analysis can be conducted, which is often challenging for individual purchasers.

What is the unit of performance?

Another contract design choice is the unit of performance calculation. For clinical areas where there are well-defined, nationally accepted quality metrics (e.g., HEDIS’s Controlling Blood Pressure), contracts should lean on those measures. These measures are often calculated at the population level—for example, the percentage of individuals in the population of interest who have achieved blood pressure control. Population-level measures are generally more administratively efficient than tying payments to each individual’s outcome, though both approaches are vulnerable to gaming.

Ultimately, the risks of perverse incentives depend less on the unit of measurement and more on how contracts are priced, whether downside risk exists, and how performance bonuses scale.

May have more interest in individual-level calculations, viewing them as more directly tied to employee experience and accountability.

May prefer population-level calculations, because of administrative simplicity and alignment with existing quality-reporting frameworks.

Key Questions to Consider When Selecting Performance Metrics for PBCs

Selecting appropriate performance measures requires careful attention to both the type of metric and its basis of evidence. While many digital health vendors present outcomes data, not all of it is meaningful and reliable. Purchasers emphasize the need for measures that are clinically meaningful, reliable, and feasible to collect.

- Clinical outcomes (e.g., BP control, HbA1c).

- Utilization/cost outcomes (e.g., ED visits, readmissions).

- Functional outcomes (e.g., mobility scales).

- Satisfaction outcomes (e.g., member experience).

Measures may capture clinical outcomes or nonclinical outcomes, such as utilization, satisfaction, or functional status. Purchasers tend to prioritize clinical and financial measures over process or experience metrics.

- Validated tools (e.g., PHQ-9, GAD-7, HbA1c) carry clinical credibility.

- Proprietary or vendor-designed tools may lack peer-reviewed evidence.

- Widely adopted, standardized measures create comparability across contracts.

Even within clinical categories, the validity of measures can vary. For example, a point-in-time blood glucose reading provides limited insight into sustained control, whereas HbA1c is a more reliable indicator of long-term glycemic management. Instruments such as the PHQ-9 for depression or GAD-7 for anxiety are clinically validated, whereas vendor-designed surveys or proprietary functional status tools often lack evidence that has proven replicability and reliability.

- Claims, EHR, device-generated, patient-reported, or vendor-collected data.

- Purchasers and vendors should agree on who controls data access and sharing.

- Clear expectations for data stewardship reduce disputes about accuracy.

Contracts should specify whether outcomes are drawn from claims data, EHR records, device integrations, or vendor-collected patient surveys. Each source carries different implications for reliability, transparency, and verification.

- Point-in-time vs. longitudinal tracking (e.g., blood pressure vs. HbA1c).

- Lagging indicators may delay reconciliation.

- Contract durations should align with the timeline for measuring outcomes.

Some outcomes inherently lag (e.g., HbA1c results every 3–6 months), which complicates contract reconciliation timelines. Others can be measured in real time but may lack longitudinal significance.

- Self-reported PROMs vs. clinician-administered assessments.

- Clinical setting vs. home-based collection (e.g., office BP vs. home cuff).

- Use of third-party administrators can increase trust and reliability.

The reliability of a metric depends not only on the tool itself but also on how it is administered. PROMs may yield inconsistent results if collected through unmonitored surveys and are more reliable when gathered by a trained assessor using standardized protocols. Similarly, some clinical measures (e.g., blood pressure control) vary depending on whether they are taken in a controlled setting or at home. Contracts should specify acceptable methods of administration to ensure that results are valid and comparable.

- Individual vs. population-level metrics.

- Inclusion/exclusion criteria for eligibility.

- Clear thresholds for engagement or outcome achievement to ensure fair compensation.

Performance must be defined in a way that is both clinically meaningful and resistant to unintended distortions. Purchasers and vendors should agree upfront on whether results are assessed at the individual or population level and clearly define inclusion/exclusion criteria for eligible members. Thresholds for engagement or outcome achievement should be transparent and standardized so that measurement accurately reflects performance and can be compared across contracts.

Explore examples of defining performance metrics

Click each clinical area to access the interactive toolkit.

Operational Components

This section covers the contract terms and processes necessary to operationalize performance-based contracts at scale, including parameters around member outreach, data-sharing expectations and infrastructure, and administrative provisions to enable consistent implementation and reconciliation.

Engagement Approach

Engagement ground rules define how vendors may contact and interact with members. Clear expectations are critical to ensure that outreach practices are effective, respectful, and aligned with purchaser values and policies.

Aim to protect member trust by setting parameters for outreach channels, frequency, and consent.

Seek flexibility to use multiple touchpoints to maximize uptake and sustain member participation.

Purchasers may seek to limit outreach frequency, require member consent or opt-in, and specify permissible channels (e.g., text, phone, mailer) to protect member trust and prevent overcommunication. Vendors value flexibility to reach members through multiple touch points and may need to tailor outreach strategies to different populations. This repeated, multimodal contact can be important to drive engagement and outcomes for some solutions.

Striking the right balance helps avoid two common risks: underreach, where members fail to engage because outreach is too limited, and overreach, where members disengage from excessive or intrusive contact. Contract terms can also address operational questions, such as if outreach should be coordinated with other communications or how opt-out requests will be honored. Ultimately, engagement rules should align with the broader objective of the contract: maximizing meaningful participation while safeguarding member experience.

Example contracting strategies for engagement approach

Click each clinical area to access the interactive toolkit.

Data-Sharing Commitments

Reliable performance measurement is foundational to PBCs. To assess whether a solution is driving clinical or financial impact, purchasers and vendors need access to timely, high-quality data and the analytic capacity to interpret them in a timely manner. This includes identifying eligible populations, establishing baselines, tracking engagement, measuring outcomes, and reconciling performance payments.

Require timely, comprehensive, and verifiable data to evaluate impact and reconcile payments.

Aim to balance transparency with operational practicality, sharing data that demonstrates value while managing privacy, interoperability, and resource constraints.

Health plans and employers differ substantially in the types of data they can access.

- Purchasers typically have access to claims, eligibility, and pharmacy data. Some also operate across distinct lines of business, which can support more tailored stratification and evaluation.

- Vendors hold more granular information about member activity within their platform, such as usage patterns, care delivery milestones, and patient-reported outcomes.

- While some large employers maintain their own data warehouses or partner with analytics firms, many rely on third-party administrators, brokers, or health plans to provide data and insights about member activity.

The information asymmetry can be problematic when vendors base outcomes on proprietary metrics, unverifiable cost-avoidance models, or narrow subpopulations of high-performers.

Case Study

Investing in Data Infrastructure to Strengthen Contracting

A global technology company has invested in data infrastructure to better evaluate, negotiate, and manage digital health contracts. Before implementation, the company conducts readiness assessments and collaborates with actuarial consultants to set realistic, data-driven performance guarantees based on historical claims and utilization trends.

After launch, vendor performance is monitored through a centralized data warehouse that integrates claims, engagement, and outcomes data. This enables the company to validate ROI in real time and adjust contract terms when needed—for example, revising communication limits that constrained engagement. The approach strengthens accountability and ensures that contracts are continuously informed by measurable results.

May prefer to receive deidentified data and/or work with a third-party data warehouse for processing and analysis.

May prefer to receive identifiable data to analyze along with claims and other data streams.

Explore examples of approaching data sharing

Click each clinical area to explore example contracting strategies and access the interactive toolkit.

Administrative Terms

The timeline required to observe meaningful improvements in clinical outcomes or reductions in total cost of care frequently exceeds the duration of most purchaser-vendor contracts. Many health outcomes and realized cost savings unfold over multiple years, but the majority of purchasers have a 12–36-month time horizon, which is why PHTI’s assessment reports contain budget impact models that are based on one- and three-year timeframes.

There are practical reasons for this relatively short time horizon: Purchasers, particularly employers, operate within constrained annual budgets and must justify new spend quickly, especially when partnering with early-stage companies that carry operational or financial risk. Workforce considerations—such as high turnover and churn in enrollment—often compress the window further, especially in industries with high turnover.

Favor shorter contracts that align with budget cycles and reduce downside risk if performance lags.

Prefer longer terms to allow sufficient time to show impact, particularly for outcomes that unfold over multiple years.

Even when purchasers recognize that a solution’s full impact may take longer to materialize, shorter contracts are often preferred as a way to manage downside risk, assess early signals, and retain flexibility.

This can create tension: Programs may be discontinued before long-term clinical benefits or cost savings can be realized, limiting both the potential impact of the solution and the ability to measure it accurately. While there are notable exceptions (e.g., some large or unionized employers report longer average tenure, as do some Medicare Advantage plans), most purchasers approach PBCs with a shorter evaluation lens, which shapes the length of contracts that they are willing to sign and the payment models they prefer.

Case Study

Embedding Audit Rights into Contracts Strengthens Transparency and Trust

Wonderful Company’s Suzanne Usaj embeds strong audit rights into all of Wonderful’s performance-based contracts. This employer requires that vendors provide claims-based ROI calculations using matched cohort methodology, with clear engagement thresholds and defined timelines for data delivery. The audit provisions included in the contract also allow the purchaser to verify reported results and trigger penalties if guarantees are not met.

In addition to the contracted period when a digital solution is offered to members, purchasers and vendors must agree on a reconciliation period for PBCs. Depending on the outcomes being measured and tied to payment, there will be a necessary run-out period for claims and other data sources to allow for validation of results and appropriate payment calculations.

Other administrative terms include expectations around reconciliation, including timelines, data sources, and validation methodology. Some purchasers include audit rights within their contracts, requiring vendors to share data and analyses—an approach that enhances accountability.

Case Study

Using Annual Scorecards to Maintain Vendor Alignment

AT&T conducts an annual evaluation process to ensure that digital health vendors remain aligned with its evolving workforce needs. Each year, vendors are scored across financial, clinical, access, and member-experience metrics, with each domain weighted differently depending on the solution’s goals. For instance, condition management tools emphasize clinical outcomes, while navigation solutions prioritize user experience and access.

Vendor-reported ROI is validated by the employer’s in-house actuarial team using internal claims data. Renewal decisions are based on the composite score rather than contractual guarantees alone, ensuring evaluations reflect strategic priorities. This consistent, structured review keeps vendors accountable and aligned with long-term goals.

Explore examples of defining administrative terms

Click each clinical area to access the interactive toolkit.

Contract Implementation

As purchasers consider the tools available to drive impact, they may want to consider how to move along the spectrum of PBC sophistication during their next contracting cycle.

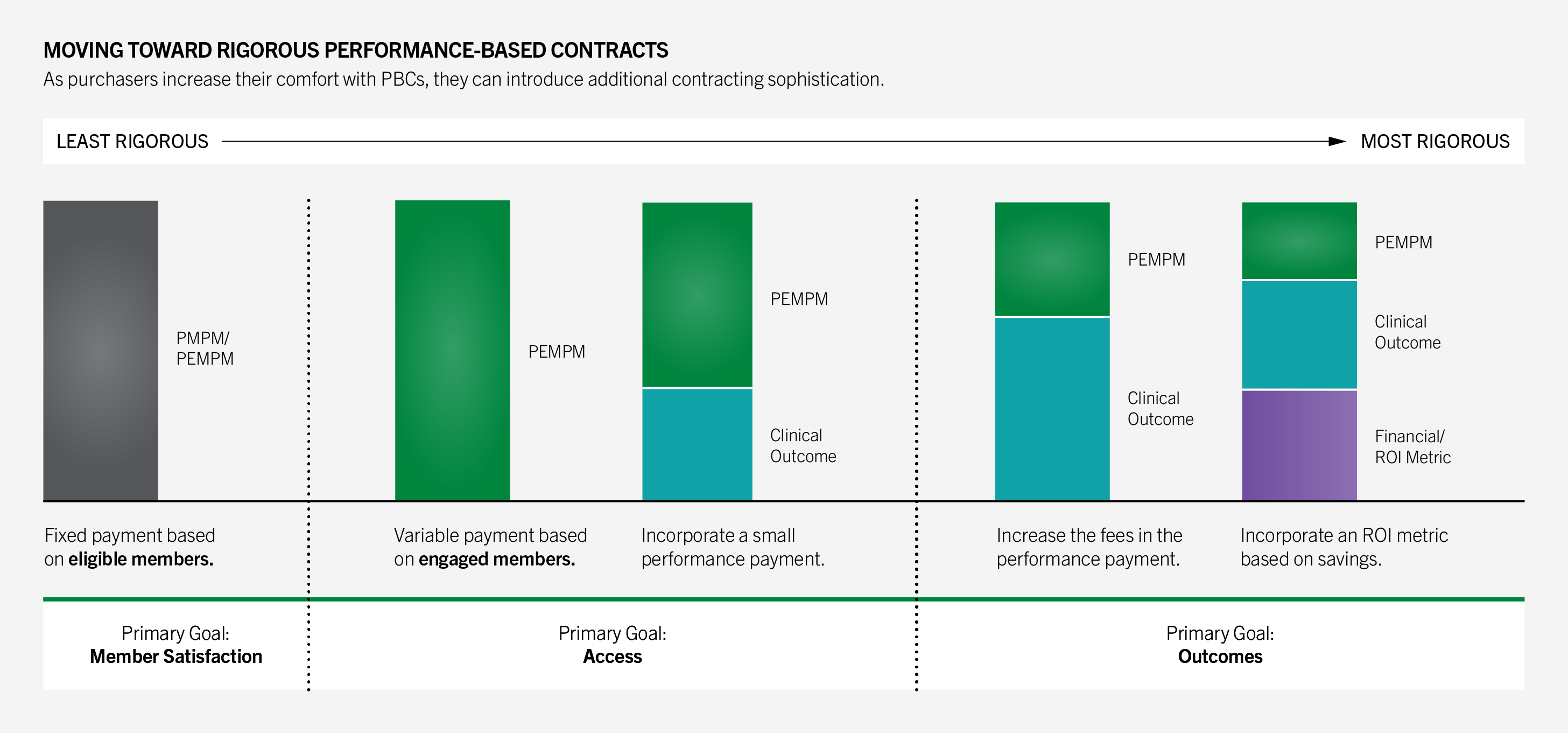

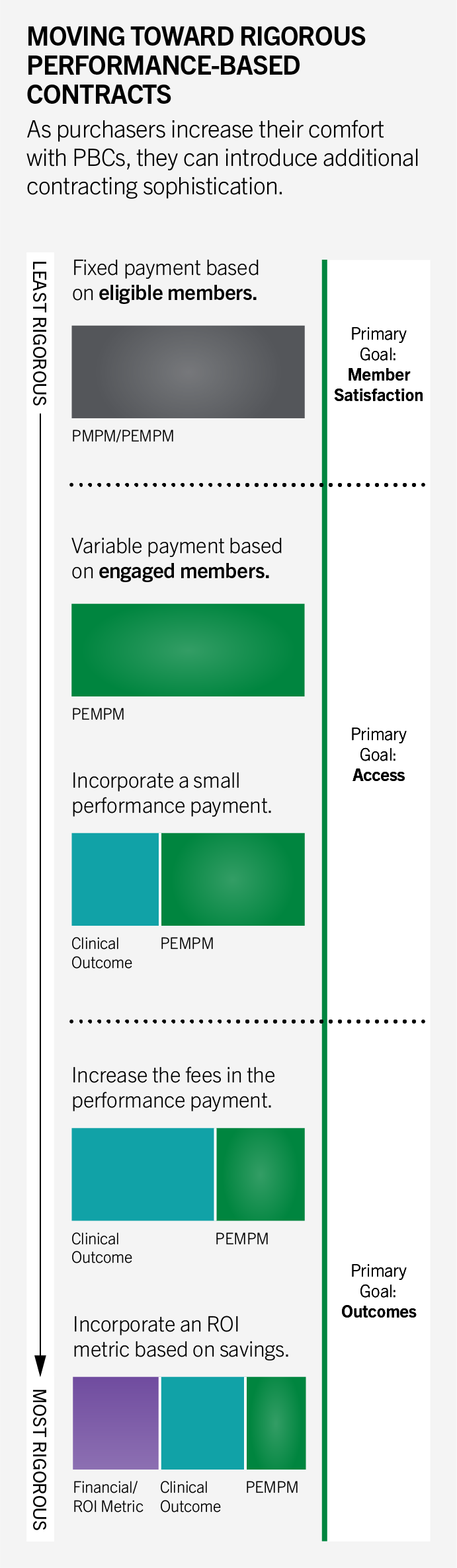

One common first step is shifting from a PMPM payment model, in which vendors are paid for all eligible members regardless of participation, to a PEMPM model. Under PEMPM, vendors are paid only for members who actively enroll and participate. While the per engaged member rate is higher, overall spend becomes more efficient because costs reflect actual utilization rather than potential eligibility.

At first, most digital health companies were charging per member per month or upfront fees. That creates a perverse incentive to sign up enough people to look successful, irrespective of outcomes. We flipped that by only getting paid if members engage and achieve meaningful clinical improvement, and we further back that investment with a 100% guarantee on claims-based ROI.

Sword

A Spectrum of Approaches

The framework below illustrates a hierarchy of approaches, from contracts focused primarily on access to those that incorporate progressively greater clinical and financial accountability. Moving along this spectrum typically involves refining engagement metrics, introducing validated outcome measures, and tying a larger share of contract value to performance.

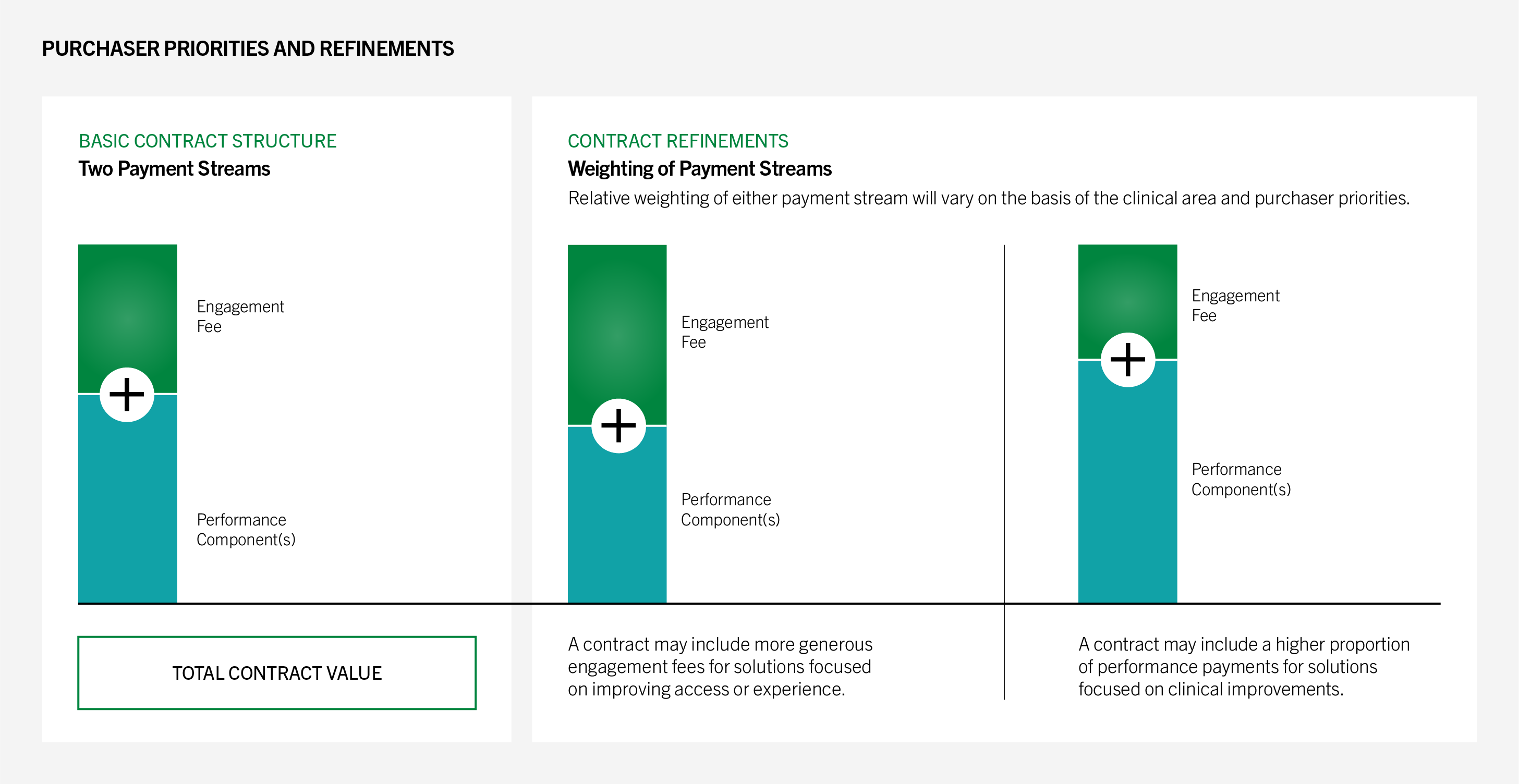

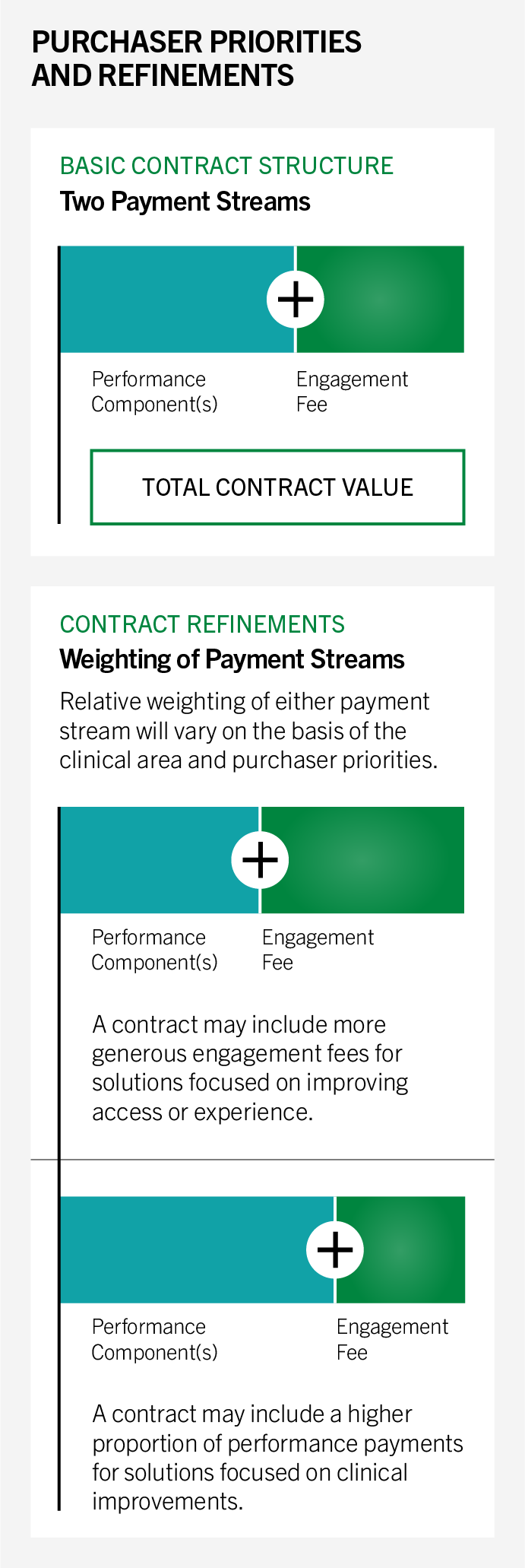

Purchaser Priorities and Refinements

As purchasers become more experienced with performance-based contracting, there are a variety of levers available to calibrate contracts more closely to goals, ranging from how engagement fees are structured to how performance components are defined.

For example, purchasers relying on “all-or-nothing” guarantees can refine contracts by introducing sliding-scale or tiered performance payments. Under this approach, vendors earn proportional rewards for incremental improvement. For instance, a contract could set 10% improvement in blood pressure control as the full bonus threshold, while still awarding partial payments if performance improves by 5–9%.

This structure creates incentives for vendors to pursue continuous gains across the population, rather than focusing narrowly on clearing a single benchmark. It also reduces friction when vendors make meaningful progress but fall just short of a cutoff, which supports stronger, long-term, purchaser-vendor relationships.

The graphic below illustrates how these choices connect to purchaser priorities and total contract value.

Additional Contract Components

- Definition of “engaged member” (e.g., opened app vs. more meaningful engagement over time)

- Engagement thresholds (e.g., payment only triggered after XX engaged members)

- Rate per member (e.g., flat, tiered)

- Payment approach: sliding scale or gating

- Definition of denominator for calculation

- Metric prioritization: split of performance payment across multiple outcomes

- Time horizon of measurement

Gaps and Opportunities

As purchasers and vendors evolve and deepen the complexity of their PBCs, two key gaps remain: appropriate step-down care models after initial goals are reached and tailoring intervention intensity to member need.

Maintenance Models

Most digital health contracts are structured around high-touch interventions aimed at achieving specific clinical outcomes. Few vendors offer differentiated “step-down” or maintenance models to support members after initial goals (e.g., improved glycemic control or weight loss) have been met.

This gap leaves purchasers with limited options: continue paying full fees for members requiring only minimal support (e.g., monthly check-ins or automated nudges) or discontinue services entirely and risk clinical regression. The lack of scalable, cost-effective maintenance models poses a barrier to sustainable performance-based contracting, particularly for chronic conditions requiring long-term behavior change.

The ACCESS Model from CMMI offers a useful reference. ACCESS includes a follow-on period after the initial intervention year for a given beneficiary, reflecting the need for continued, lower-intensity support to sustain outcomes. The model differentiates goals during this period: bringing members who remain out of control into control, while maintaining outcomes for those already in control.

PHTI recommends a similar approach in commercial PBCs when clinically appropriate for the condition. When average beneficiary engagement with a solution exceeds a year and further engagement or maintenance is clinically indicated, vendors should develop and validate structured maintenance offerings and contract with purchasers at a lower price point to ensure continuity of care and long-term clinical improvement at a commensurate cost.

Triaging Lower Acuity Patients

Many digital health solutions target broad populations but few incorporate structured triage processes to direct lower acuity members to lighter touch or self-guided support. As a result, vendors may deploy high-cost clinical resources for members who could be effectively managed through automated tools, brief coaching, or primary care integration.

This lack of stratification creates tradeoffs for purchasers: continuing to pay for intensive services that exceed member needs or excluding lower acuity members altogether, limiting overall reach and engagement. Without clear criteria for triaging members by clinical severity or risk, contracts struggle to balance access, cost, and measurable impact.

PHTI encourages vendors to design and validate tiered care models that align resource intensity with member need, such as integrating automated monitoring or brief intervention pathways for low-acuity populations.

Conclusion

As digital health continues to redefine care delivery, performance-based contracting is no longer aspirational, it is expected. However, realizing the full potential of these contracts requires thoughtful design, shared commitment to transparency, and scalable infrastructure for evaluation.

This report provides a practical roadmap to help stakeholders navigate that complexity, align incentives, define meaningful outcomes, and create pathways to scale. The tools and case studies shared are designed to help purchasers and vendors move from theory to execution and from isolated pilots to sustainable models that work at scale.

As the market evolves, success will hinge on treating contracting as a collaborative partnership rather than a one-time transaction, bringing together innovation and accountability to ensure that digital health solutions not only promise transformation, but consistently deliver it.

Contributors

PHTI is grateful to the 50+ individuals and organizations who shared their time, expertise, and perspectives throughout this project. This included various members from the PHTI Purchaser Advisory Council, PHTI Digital Health Collaborative, as well as brokers, consultants, data analytic companies, industry experts, and digital health companies from organizations that included but were not limited to: 32BJ, Abett, Amtrak, AT&T, Blue Shield of California, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, BJ’s Wholesale Club, Cadence RPM, CVS Health/Aetna, Delta Airlines, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Geisinger, Headspace, Health New England, Highmark, Humana, Lantern, Limber, Meru, Ochsner, Spring Health, Sword, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Virta, WTW.